Welcome to Postcards from New Mexico! Two Sundays a month, I share beauty, stories, and culture from this region that has been my home since 2008. Please consider upgrading to a paid subscription and enjoy these benefits:

A genuine snail-mail postcard from New Mexico!

Access to the “If you go/Local’s Tip” section of certain posts, where you’ll find valuable information to enhance your next journey to Northern New Mexico.

In acknowledgement of living on un-ceded Tewa lands, a portion of your paid subscription will support Native-led nonprofits doing good work in this region.

p.s. You might also enjoy my other Substack newsletter: The Practice of Life

"The Revolt period is still so important to Pueblo identity. In many ways it shaped the world we live in today... I always wonder how the Pueblo would live today if there had been no Revolt. It’s a scary thought, because if those colonial practices had played out over the course of another century, there’s no telling what the state of my pueblo would be. We are living where we are and we are the people we are thanks in part to the Revolt.”

- Joseph Aguilar, archaeologist and member of the Pueblo of San Ildefonso

Today’s postcard is about one of the most important historical events to ever take place in Northern New Mexico, but one that few tourists to this area (and even non-Native residents) are aware of. Many come to this region and appreciate the strength of Indigenous culture and spirituality without understanding what it's taken to uphold this lineage in such a strong, clear way. So let’s take a few moments for some learning…

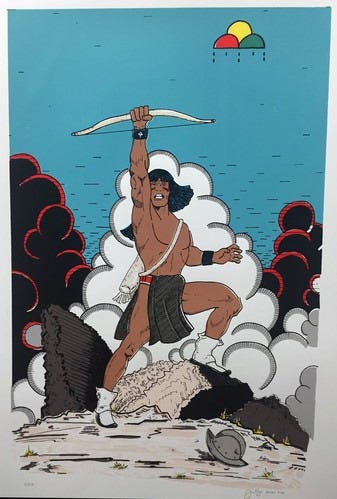

On August 10, 1680, 46 villages of the Northern Rio Grande area rose up in a united show of strength against the violently oppressive occupation of the Pueblo homelands by the Spanish. The Pueblo Revolt, as it is known, was the first successful revolution against colonization in Northern America. The Indigenous people of the Northern Rio Grande region, organized and led by Po’pay of Ohkay Owingeh and White Elk from Picuris Pueblo, succeeded in driving out the Spaniards for 12 years, a truly remarkable feat given the nearly century and a half of oppression they experienced.

This act of revolution was a long time in coming. From the start of the Spanish occupation of this area in 1540s, the colonial power exerted its domination over the people here through many means, including physical violence and murder, slavery, economic exploitation, restricting access to fertile farmlands, and suppression of religious beliefs and practices. As you can imagine, the suffering generated from these practices was immense.

In the 1670s, the region was wracked by a severe drought which caused a famine among the Pueblo people, increasing tensions and leading to great unrest. In 1675, the Spanish governor of New Mexico ordered the execution of several Pueblo holy men and the public whipping of many others, including Po’Pay. Over a period of a number of years after this, Po’Pay, White Elk, and others came together to pray and consider what needed to be done to protect their people and their way of life. Faced with the complete loss of their culture and having exhausted other means of resistance, the Pueblo people chose to organize a militant resistance. Further away from the river area, the Pecos, Zuni, and Hopi people also chose to commit to the revolt.

Leaders set a date for the rebellion in August of 1680. Runners carrying knotted cords of yucca plants were sent to each Pueblo, with the cords serving as a kind of calendar representing the number of days until the uprising. Every morning, the leaders untied one knot from the cord. When the last knot was untied, it was the signal to act in unison.

This was not a bloodless revolution; given the conditions, there was no way it could have been. About 400 Spanish were killed, including 21 Franciscan missionaries. The survivors fled south first to Santa Fe and subsequently to El Paso.

Even after the Spanish returned in 1698 under Don de Vargas, the Pueblo Revolt helped ensure the survival of Indigenous cultural traditions, lands, languages, and religions. The strength and brilliant organization they showed in 1680 was not forgotten by the Spanish, who recognized the 19 Pueblos as independent nations with sovereign cultural and religious traditions.

The thing is — even though this is history that took place more than 300 years ago, it is still vitally alive to this day. It has informed how Indigenous people here think of themselves, and serves as a beacon for people everywhere to draw on the strengths of their spiritual and cultural identity in the face of the brutal forces of colonization, which exist to this day.

“The legacy of the Pueblo Revolt serves as a powerful reminder of the strength found in community and what can happen when we organize and face our oppressors as one.

We uplift the profound leadership and community organizing happening throughout Pueblo communities today. It is through their amazing leadership and dedication to the people that they continue to illustrate the dreams and visions of their ancestors.”

Learn more about the Pueblo Revolt:

The Indian Pueblo Cultural Center’s Resource Page on the Revolt

and this 20-minute video is well worth your time…

I didn't learn of the Pueblo Revolt until I lived in Las Cruces in the 1990s and began walking the Tortugas Pilgrimage every December with my dear friend, Denise Chávez, poet, novelist, playwright and activist. I have wondered ever since why we don't celebrate it as a state holiday, but I guess the answer is what you wrote: the Pueblo Revolt was a tremendously effective and courageous strike at the heart of colonialism, and the colonists are the ones who write our history.

Thank you, Maia. Growing up in NM as ethnically northern European shaped my view of myself and the long view of American history. Nothing can replace a visit to Acoma Pueblo or seeing the conquistadors inscriptions from 1500s at El Morro rock. I have a dear Pueblo friend from elementary school in touch on social media decades later and am grateful for the humility of growing up on someone else's land surrounded by someone else's language, and walking mesas rich in desert botany daily to get to public school.